- Published on

A Non-Zealot Case for Crypto

- Authors

- Name

- experience

- @trustlessexp

Disclaimer: I own some cryptocurrencies. I will not name any particular cryptocurrency in this post, deliberately focusing on underlying concepts. This is not because these concepts have not been already implemented, but simply because I do not want this to turn into a promotional piece. If someone is interested to discuss examples, feel free to @ me on Twitter.

Anyone following the crypto ecosystem the past few years has probably noticed a large increase in the number of crypto skeptics. David Gerard, Amy Castor, Stephen Diehl or Ben McKenzie, these prominent figures have been strongly arguing about the perils of cryptocurrencies, including in the form of books either alredy released or in production.

In the wake of this criticism I have also noticed the rise of a particular line of argumentation that consists in saying that all of crypto supporters (or "crypto bros") are libertarian extremists and conspiracy theorists sociopaths who advocate for hyperfinancialization of everything, which would turn society into a dystopian hellscape of human exploitation and instability.

I cannot blame them for thinking this: when listening to some of the most vocal crypto proponents, there's an unshakable feeling that this sector is essentially a cult, both in form and content.

Supposedly, crypto will solve inequalities, world hunger, replace governance systems and we'll live in a perfect utopia all plugged into the metaverse.

I would like to detach myself from such discourse and take Stephen Diehl up on his offer to explain "why Keynesian social democrats shouldn't outright reject the entire premise of [cryptocurrencies]".

As part of this effort, I would like to start by stating some of my political and related beliefs so as to make sure that the content of this blog post may not be discarded on the ground of me supposedly being a libertarian maximalist:

- A democratic government is desirable

- A welfare state is desirable to provide basic decency for every member of society

- Critical public infrastructure is desirable

- Markets are not always efficient

- The state can have a role in correcting market inefficiencies

- Government issued currency is useful to fulfill the above goals

- Crytocurrencies are not going to replace fiat currencies

- Cryptocurrencies are not going to replace banks

- Most cryptocurrencies are not good forms of currency

- Cryptocurrencies are not going to magically "bank the unbanked"

- Distributed ledgers will not revolutionize the supply chain and solve logistics

- Environmental damage from Proof-of-Work blockchains is a concern

- "Crypto fixes this!" -- No it doesn't

- "Web3" shouldn't replace the entire internet infrastructure backbone

This blog post aims to make the argument that one may consistently hold these views while at the same time consider that there is some useful innovation in the digital asset space.

In particular, I will focus on how permissionless distributed ledgers may provide more robust and transparent financial infrastructure. In this framework, holding a certain type of cryptocurrencies may be a legitimate bet on future earnings as opposed to strictly a short term ponzi.

My hope is not to convince skeptics in the span of a single essay, but rather to encourage good faith discussion around a specific set of arguments pertaining to digital assets, without always falling into the trap of focusing on the nonsense coming from cultists.

Is Finance Fundamentally Bad?

In order to make this piece self contained for readers with no knowledge of finance. It is easy to get the impression that finance is just about maxing out on $GME with leverage to gamma squeeze investment funds, akin to a casino, and with this representation one would wonder why we should care about financial infrastructure.

If we leave aside the jargon and degenerate bets for a moment, we find that the idea of dividing the capital of a certain productive entity into shares representing fractional ownership of the company and its future profits is quite innocuous.

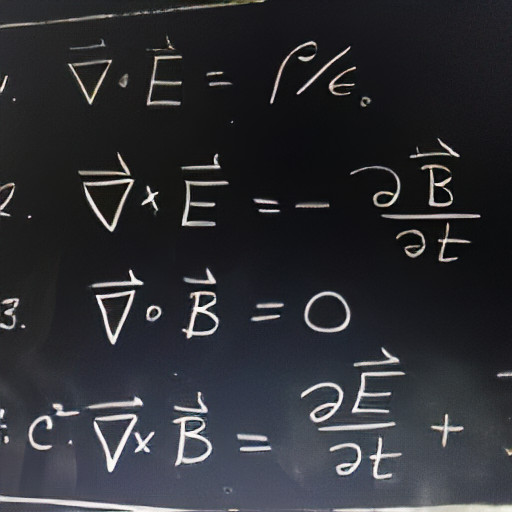

How does any of this make sense??

The value of these shares, although fluctuating under short term speculations, is fundamentally rooted in present value or future earnings. Venues like NASDAQ or the NYSE are simply facilitating the exchange of such shares, thereby letting investors obtain or sell ownership of a given company. Much of our current system relies on companies sharing their profits via such instruments.

Similarly, synthetic products based on real underlying commodities like oil may appear like gambling on the surface. Is there any actual real world use to the idea of betting on the future price of the Brent, or is it just like going to the slot machine?

As you might have guessed, this may also be fundentally useful if we introduce the concept of hedging, or in other words seeking insurance.

Consider a transport company running on a tight margin because of a significant fuel budget to power its truck fleet. Say a considerable geopolitical crisis erupts that signficantly increases the cost of fuel, a war for example. Suddenly, this company is not profitable anymore and depending on their liabilities may go bankrupt very quickly. Had the company bought a long position in oil futures markets (which for the uninitiated simply means that they would have bet the price of oil will increase), they would have profited from the situation, and these gains may help offset their increased operational costs, thereby delaying bankruptcy, or avoiding it completely.

This is what finance is fundamentally about: profit sharing from tangible production of a service or good, and insurance. More complex constructs like options are simply reframing this in different ways to make it more convenient to express certain beliefs on future valuations or seek perfect insurance.

So what's the big deal about hyperfinancialization and what about crises like the 2008 subprime disaster? Where does this go wrong?

To understand this, let's briefly dive into the world of fraud and why regulation might be desirable.

Why regulations?

If we go back to an unregulated world before the digital age, we can easily see why fraud might easily arise from the buying and selling of the financial products described above.

A broker might tell you about an amazing company that is supposedly generating a ton of profit. To convince you they'll show you some marketing material, testimonies of other shareholders and they may even let you take a look at the books of the company.

There's a problem though: how can you trust that any of it is real? Are these eight chests of gold, or stones with a thin layer of gold?

As an individual, you certainly won't travel to the company warehouses to check on their operation, and don't even think about opening their vaults and counting for yourself how much money they have.

So the broker can just lie about pretty much everything, and they can even start giving dividends coming from new investors to give you the impression that there is indeed a profitable business underlying these shares: this is a Ponzi scheme.

Charles Ponzi is not bad looking in this photograph, but don't judge a book by its cover: that's a scammer.

There may be countless variations of such fraudulent activity. Another example would be bucket shops which are described as follows by Balleisen in Fraud: An American History from Barnum to Madoff:

operators often only pretended to execute the trades ordered by their customers, shaved off profitable returns through false reports on actual trades, and reported initial phantom profits on investments in order to attract more substantial deposits.

In this context, some level of regulations makes sense. Theoretically, the government fulfills its fundamental role of enforcing legal contracts between individuals and/or corporations. Some rules are defined for what a "bank", "stock exchange" or "derivatives market" are and how they should operate. Entities that wish to conduct such business must seek registration, which comes with reporting and auditing requirements. In the US today for example, this is the role of the SEC, CFTC, OCC etc.

With this in mind, you don't have to go to the company warehouses yourself, or trust some vague rumor such that you end up falling into a ponzi trap: if you trust the democratically elected government and its institutions, you just need to stick to these regulated marketplaces, and you'll probalby be fine.

In that sense, "trusted intermediaries" is not a bad word. These intermediaries serve the purpose of preventing fraud by conducting the required checks at the different steps of a particular transaction.

But as we will see, this device is not infallible, and comes with some drawbacks.

Fallibility and inefficiencies

As history has demonstrated, the regulations described herein are not infallible. The 2008 subprimes crisis may be resumed as obfuscation of re-hypothecated, unsecured subprime loans in order to build a house of cards.

Investigating such complex schemes is costly for the government. While disclosures and audits are required, the books may still be cooked, such that it can take a long time for law enforcement to figure out the truth.

Further, select government entities may be transiently corruptible, something that even the most ardent crypto skeptics agree on. This may be caused by revolving door politics, conflicts of interest or other factors. For a government to keep working as intended, it must be able to root out corruption within its own ranks efficiently, a task which is not always easy.

Financial regulations also come with practical drawbacks. Because it relies on a few trusted intermediaries, settlement is far from instantaneous and operations can be costly.

Additionally, the initial legal costs in order to seek registration and compliant costs during normal operations favor already registered incumbent and don't foster healthy competition. This is another area where the transient corruptibility of the government may hurt.

Here I would like to emphasize that the above is not a claim that regulations or the government are always bad, but simply remarks on possible improvement areas. In short, the current financial infrastructure is still more opaque than one may desire, and lacks interoperability and efficiency in some respects.

Potential role of permissionless ledgers

This where some people, including me, see a potential role for permissionless distributed ledgers: more transparent and efficient financial infrastructure plumbings. This is what we shall focus on in this section: not on the idea that every individual will replace their online accounts with crypto wallet, not on the idea that the music industry will be "disrupted" by web3, neither on the idea that crypto will replace fiat. Here we're strictly interested in what has been termed "decentralized finance" or DeFi.

Firstly and despite many flaws, some of the currently deployed distributed ledgers are, in fact, incredibly transparent. When a particular protocol is hacked or goes underwater because of operational difficulties, when a project is controlled by the founders instead of being truly non-custodial and decentralized, or when a "rug-pull" occurs, everyone knows about it almost immediately.

There is no delay, no investigation needed, the very nature of the ledger being open for everyone to see means the books can't be cooked by the fraudsters. This doesn't include products that interface with the real world like Tether for which the Wildcat Banking comparison is quite apt: these should still be regulated.

In the world of crypto, ponzis are transparent. One may just inspect the reserves of the ponzi protocol and notice that they are only being re-filled by new entrants, or that a particular protocol is running at a loss by massively subsidizing its usage with a useless digital coin.

Importantly, it is not just validators of the network who can inspect the state of the ledger. Anyone may run a node, i.e. a piece of software that connects to the network and checks that it is operating according to the rules of the protocol. This means that contrary to some grandiose statements, the system is not fully automated and trustless, there is still a need for social coordination to choose which specifications and which fork of the ledger are canonical.

Full analysis of a hack... 3 hours after it occurred. The project cannot cook the books to hide the hack, as everyone can see the books.

This level of transparency is significantly different from the situation described previously where a "shadow bank" customer has no ability to inspect the actual reserves of the service they use. Because of this fundamental difference, one may reasonably relax some of the regulatory constraints. In particular, this allows for disintermediation at specific steps in a transaction.

On-chain decentralized exchanges are a good example of this. A constant function market maker for example has a pool made of a mix of asset A and B. Users who desire to acquire B come and deposit A into the pool. The pool uses a simple formula to find what amount of B the user should get. This happens in a single transaction during which the user did not have to trust any intermediary. It can be shown, for example in this paper from Financial Conduct Authority's economist Peter O'Neill, that this level of automation offers some benefits.

Other financial constructs can be similarly automated such as decentralized lending protocols which have been studied in academia or derivatives trading platforms, some of which are reviewed in this paper or in the annual review of the St. Louis Federal Reserve from the same entity for a more complete overview.

Trustless?

While a majority of existing protocols only pretend to be decentralized while being actually controlled by developers, some of them are in fact not owned by anyone and immutable, such that one does not have to trust that the owner won't become corrupt.

This addresses concerns that even some of the entities we trust today may become corrupt in the future and gives rise to the property of "trustlessness". To define "trustless", we can use the definition of Charoenwong et al.:

All smart contracts run on a public computation platform where we can read the code, run it ourselves, and monitor all transactions in plain view. Further, if there is a conflict within the system – say a block of code has more than one valid interpretation – the system itself contains a conflict resolution mechanism which we can observe in action. Trustless means that we can verify everything for ourselves and safely rely on our own computations.

Once such a decentralized, trustless protocol is deployed, access to it is universal. Anyone in any country is free to use it or build upon it. The protocol does not discriminate since it has no owner. While some protocols pretend to not have any owner, this fact is publicly known as previously discussed.

Contrary to some claims, finance built on transparent distributed ledgers does not obfuscate and make things more complex, it simplifies them. Re-hypothecation as seen in the 2008 subprimes crisis could not happen without instantaneous warning signals on such transparent rails.

The end goal here may be resumed as follows: making financial infrastructure a common good, a global settlement layer allowing for broad interoperability and transparency.

This is not an internet replacement: it is built on top of the internet, and strictly targets key areas of finance. Similar to the internet however it would become a neutral layer. Because of the ability for anyone to run a node, any deviation from such neutrality (censorship by a subset of validators) may be swiftly punished.

Permissionlessness means that validators may freely come and go as they choose, and anyone may freely interact with the ledger, either to deploy new applications or as users. This makes supporting the network a competitive market with a role analogous to internet ISPs.

Non-ponzi expectations

A network functioning as described above provides a service, and similar to how the Intercontinental Exchange is valuable because of the clearing services it provide, it may accrue value in the form of fees paid to validators by users to obtain economic bandwidth.

Of course, apart from a very limited number of examples, there are currently no real world assets on distributed ledgers. However this does not preclude the possibility of such integration, and it is indeed the end goal for many finance minded enthusiasts.

As such, someone buying a certain class of digital assets may not just be participating in a ponzi, but rather have a meaningul expectation of future profits for a particular economic model centered around distributed ledgers hosting more transparent and efficient financial infrastructure services.

This idea is not anti-state, and there is no claim that the entire internet should be replaced by this technology. This expectation of future profits may be proven wrong, but it is not baseless, nor is it inconsistent with the political views I gave as a premise.

Because these platforms are permissionless however, there are in fact many grifters who use it to scam others, similar to how the internet itself is used for countless scams besides other legitimate uses. Combatting these scams is of course desirable.

Interfacing with real world regulations

Decentralized finance cannot exist in a vacuum in my opinion. If this infrastructure is never used to support real world assets transactions, then it will remained a closed ecosystem of digital tokens with no footing in reality.

In order to support real world assets, the role of governments cannot be ignored. One cannot possibly imagine that companies will start issuing shares directly on distributed ledgers without governments having a say.

Clear regulations are needed in order to bring real world assets on-chain so that they would be able to leverage this more transparent and efficient financial infrastructure. This includes companies that purport to hold reserves of some fiat currency and issue tokenized representation of it on-chain. Companies like Circle and Tether should be regulated so that these claims may be verified.

Governments also have a role in regulating exchanges like Coinbase or Kraken, which as centralized entities are susceptible to the same type of fraud discussed previously: when it comes to them, a user can hardly go to the exchange and inspect their book, or have any kind of guarantee that they'll honor trades or withdrawals.

Unfortunately, there are still some areas where the concept of trust is unavoidable, and wishful thinking does not make the problem go away, it just means wasting time reinventing the wheel.

Limitations

There are of course some important obstacles along the way to using this new financial infrastructure for a broad range of real world assets.

Theoretical limits

For some definition of scalability, a recent article claims that decentralized ledgers may not be able to scale without occasional failures.

There are also some doubts on the ability for this type of platforms to deliver trustless positive risk-free rate.

Discussion of these results is left to a future publication but in short, I do not believe that they are incompatible with the vision outlined herein. Positive risk-free rates for example may be necessary to support the entire economy as we know it, but this is not what DeFi purports to do in our framework.

Smart contract risk

Furthermore, there is a risk of bug in deployed smart contracts which may cause significant losses for users.

The past few years has seen a cambrian explosion of deployed smart contracts. As argued by David Gerard, the complex nature of coding robust financial applications, the adversarial nature of permissionless blockchains, and the time-to-market incentives inherent to a speculative bubble combine to significantly increase the probability of exploits.

As we have seen before, the transparency of these systems allows us to detect and report on these exploits effectively.

This seems like it would preclude any use of DeFi infrastructure for serious assets, but I believe the picture is more nuanced.

Firstly, the hacks we do hear about once per week are typically from applications which are known a priori to be extremely risky by all market participants, and/or protocols deployed by teams that obviously do not invest in security.

There are in fact developers in the ecosystem that invest significantly in security, such that some of the major protocols have held large cumulative value of funds without suffering any hack for the past 4 years.

This creates an inverse survivorship bias: because anyone with an internet connection can deploy a new smart contract, there are hundreds of them that were developed or copied by solo developers lacking required skills which inevitably get hacked, and this noise drowns the few protocols that are in fact developed with great care and security investment, without rushing because of time to market concerns.

Secondly, a lot of the security concerns are related to the Turing completeness of many smart contract platforms and the lack of proving tools for the programming languages use. Here we simply note that this is not a necessity, and that some smart contract platforms are indeed working on non-Turing complete languages which may be used in conjunction with formal provers for smart contracts.

Finally, while the risk may still exist even with an overabundance of precautions, it can be modelled and insured against. This may be yet another important area where centralized institutions may have a role to play on top of the decentralized common good infrastructure.

Thus we see that despite these important limitations, one may still have a legitimate expectation of future usage for high stakes real world assets.

Conclusion

In this article, I have not made claims that cryptocurrencies are solving all problems of the modern internet, that everyone will have a crypto wallet and live in the metaverse, or any of the other usual grandiose claims.

The focus was solely how distributed ledgers may make financial infrastructure a transparent, global common good.

I believe this goal is not libertarian, nor is it affiliated with Austrian economics in any way, and that it is not incompatible with the views I shared at the beginning of the article which are by and large favorable to the idea that a democratically elected government is overall good.

Some currently deployed platforms can boast a solid track record without any hacks, and despite some theoretical concerns about cascade liquidations potentially creating bad debt, major on-chain collateralized lending platforms have been shown to be able to endure the extreme stress of a 60% crash both empirically and with robust agent based modeling.

This is enough ground for a reasonable expectation that this evolution in financial infrastructure may be used for real world assets in the future.

In this framework, being long a specific class of digital assets can reflect a legitimate expectation of future profits as opposed to simple participation in a ponzi game. This expectation may be wrong, but the speculation is not baseless.

I hope that this article can sway the debate between skeptics and a subset of digital assets proponents to focus less on the most outlandish, cultish claims, and more on topics of common ground that deserve good faith technical discussions.